Scientists create and control 'cyborg' moon jellyfish to study changes in Earth's oceans

The ocean covers most of our planet, yet much of it remains out of reach. Scientists have long struggled to study life in the deep sea. Robotic equipment is expensive, and people cannot dive to extreme depths.

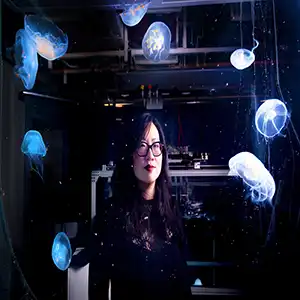

These issues leave entire marine ecosystems unexplored. Nicole Xu, an engineer at CU Boulder, is confident that her lab’s “cyborg” moon jellyfish can help.

These sea creatures, also known as Aurelia aurita, are simple but remarkable. They move with little effort, pulsing gently as their translucent bells expand and contract. Their tentacles drift behind them like threads, yet every motion is purposeful.

Creating “cyborg” moon jellyfish

Xu has watched jellyfish for years, first as a fascinated student and now as a researcher. She studies their movements not just to admire them, but to put them to work.

Her team attaches small electronic devices to the animals. These devices stimulate their muscles and allow researchers to steer them. Soon, the system may carry sensors to track temperature, acidity, and other ocean data.

That could send jellyfish into places humans rarely reach, and return information that is otherwise too costly to gather.

“Think of our device like a pacemaker on the heart,” Xu said. “We’re stimulating the swim muscle by causing contractions and turning the animals toward a certain direction.”

Survival through 500 million years

Climate change is hitting the ocean hard. The water is getting warmer and more acidic as carbon dioxide levels rise.

Marine life struggles to adapt, and many species are in danger. Scientists need to measure how these changes unfold.

The challenge is scale. The ocean is vast, deep, and unpredictable. Sending ships or robots everywhere is simply not possible.

That is where jellyfish stand out. They are some of the most energy-efficient creatures alive. They have survived in their current form for more than 500 million years.

Moon jellyfish are ideal explorers

Jellyfish don’t have a brain or spine, but their basic organs and nerve nets keep them moving.

They also lack nociceptors, so they don’t experience pain the way humans do. Their stings cannot break human skin, which makes them easier to work with.

Moon jellyfish live in many environments. They often float near shorelines where food is abundant. But they also dive to extreme depths, even as far as the Mariana Trench, 36,000 feet (10,900 meters) down.

That range makes them ideal for exploration. Xu first tested her biohybrid jellyfish in 2020, guiding them through shallow waters near Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

“There’s really something special about the way moon jellies swim. We want to unlock that to create more energy-efficient, next-generation underwater vehicles,” she said.

Learning how moon jellyfish work

Xu’s lab doesn’t only focus on movement. She and her team study how jellyfish push water as they swim. To see this, they fill tanks with biodegradable particles like corn starch. They then shine lasers through the water.

The particles light up the flow patterns created by the jellyfish. This approach replaces older methods that used synthetic tracers such as glass beads. Those tracers were more toxic and less sustainable. Corn starch is safer, cheaper, and better for the animals.

Her group also works on improving steering in natural ocean conditions. The open sea is far less predictable than a lab tank, so making the technology reliable outside is a big step.

Xu believes these advances can lead to new tools that draw ideas from nature rather than replacing it. But the research is not only about technology – it also raises ethical questions.

Caring for moon jellyfish in labs

For many years, scientists believed invertebrates could not feel pain. New evidence now suggests that some may react to harmful experiences.

That means researchers must think carefully about how their experiments affect the animals they study. Xu takes this seriously.

She watches for signs of stress in her jellyfish. Stress usually causes them to produce extra mucus and stop reproducing.

Her jellyfish show none of those patterns. Instead, they seem to be thriving. Inside her tanks, baby polyps the size of pinheads are growing, with tiny tentacles starting to appear. That growth suggests the jellyfish are healthy and reproducing naturally.

“It’s our responsibility as researchers to think about these ethical considerations up front,” Xu said. “But as far as we can tell, the jellyfish are doing well. They’re thriving.”

Jellyfish as ocean allies

Jellyfish may look simple, but they represent a major shift in how humans can explore the ocean. By combining engineering with biology, Xu’s work shows that living creatures can serve as allies in research.

They move efficiently, survive in extreme environments, and carry little risk to humans. Outfitted with sensors, they could one day map parts of the ocean we know almost nothing about.

This is not science fiction. Xu has already proven the concept in the field. Her next steps include refining the technology and expanding its capabilities.

She sees jellyfish not only as data gatherers but also as inspiration. Their effortless swimming could shape how we design future underwater vehicles.

Rethinking research tools

The idea challenges how people think about research tools. Instead of building larger machines, we might adapt what already exists in nature. It is efficient, elegant, and potentially transformative.

At the same time, Xu insists that ethical care for the animals must remain at the center of this work.

Her project stands as a reminder that progress and responsibility can go together. The moon jellyfish, a creature that has floated through Earth’s waters for half a billion years, may now help us understand how those waters are changing today.

The study is published in the journal Physical Review Fluids.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–